As I'm gearing up for the publication of Aesop’s Fables in Latin: Ancient Wit and Wisdom from the Animal Kingdom (coming soon from Bolchazy-Carducci!), I'm reviewing the different Perry numbers that will be included in that book. For each of the fables, I'm posting here a Latin version of the fable along with an illustration that can be compared/contrasted with the version in Barlow's book.

Today's fable is Perry #503, the story of the rooster who found a precious gem in the manure. At the Aesopus wiki, you can see a complete list of the versions of this fable that I have collected. This is an extremely well-attested fable in the Latin tradition, dating back to the poet Phaedrus. In the medieval collections based on Phaedrus, this fable often appears first in the book.

One of the most interesting things about the fable is the way it can lead to two very different morals. In Phaedrus, for example, the rooster is a fool who cannot recognize the real value of something he sees right in front of him - and for Phaedrus, this is an allegory of his situation as a poet, when foolish readers cannot appreciate his poems! In other authors, however, the rooster is a wise creature, who understands that jewels are far less useful than foodstuffs, and the fable is thus an endorsement of the pleasures of a simple life as opposed to the uselessness of wealth and luxury.

The version in Steinhowel's Aesop follows Phaedrus, where the pearl is a precious object, unluckily lying in a dung heap and discovered by a rooster who cannot appreciate her:

In sterquilinio quidam pullus gallinatius, dum quaereret escam, invenit margaritam in loco indigno iacentem, quam cum videret iacentem sic ait, O bona res, in stercore hic iaces! si te cupidus invenisset, cum quo gaudio rapuisset ac in pristinum decoris tui statum redisses! ego frustra te in hoc loco invenio iacentem, ubi potius mihi escam quaero, et nec ego tibi prosum, nec tu mihi. haec aesopus illis narrat, qui ipsum legunt et non intellegunt.

Here it is written out in segmented style to make it easier to follow, while respecting the Latin word order:

In sterquilinio

quidam pullus gallinatius,

dum quaereret escam,

invenit margaritam

in loco indigno iacentem,

quam cum videret iacentem

sic ait,

O bona res,

in stercore hic iaces!

si te cupidus invenisset,

cum quo gaudio rapuisset

ac in pristinum decoris tui statum redisses!

ego frustra

te in hoc loco invenio iacentem,

ubi potius mihi escam quaero,

et nec ego tibi prosum,

nec tu mihi.

haec aesopus illis narrat,

qui ipsum legunt et non intellegunt.

Notice the nice play on words with legunt and intellegunt there in the moral!

Meanwhile, for an example of a version which praises the rooster for his wisdom, here is Sir Roger L'Estrange's English version:

As a Cock was turning up a Dung-hill, he spy’d a Diamond. Well (he says to himself) this sparkling Foolery now to a Lapidary in my place, would have been the making of him; but as to any Use or Purpose of mine, a Barley-Corn had been worth forty on’t.

THE MORAL He that’s industrious in an honest Calling, shall never fail of a Blessing. ‘Tis the part of a wise Man to prefer Things necessary before Matters of Curiosity, Ornament, or Pleasure.

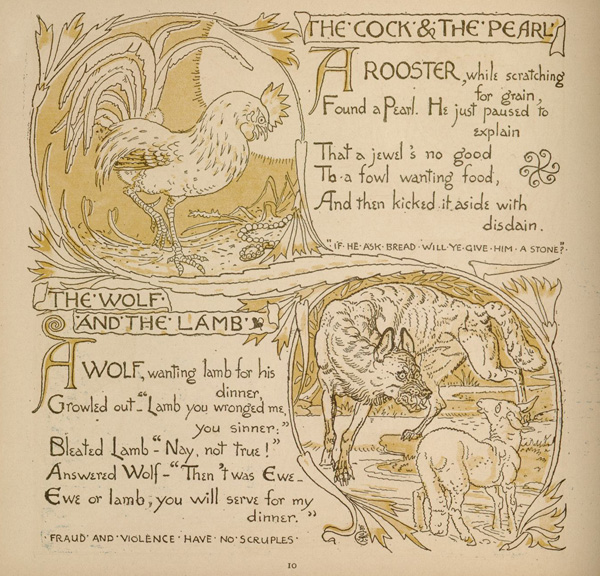

For an image of the story, here is an illustration from Walter Crane's Aesop which tells the story in limerick form!

Some dynamic content may not display if you are reading this blog via RSS or through an email subscription. You can always visit the Bestiaria Latina blog to see the full content, and to find out how to subscribe to the latest posts.

2 comments:

Very nicely laid out and presented; I thank you for the educated introduction to Phaedrus.

Thanks for your note! Phaedrus is really a fascinating case - probably more than any other known "author," he influenced by the Aesopic tradition by introducing a strong sense of moral indignation that you will not find in traditional Aesop materials or in other literary authors (such as Babrius or Avianus). Then, as Phaedrus himself became "traditionalized" in the medieval transmission of his materials, that moral tone exerted by the author of the story himself became a characteristic feature of many later Aesopic collections. We are so lucky indeed that Phaedrus chose Aesop as his field of poetic endeavor! :-)

Post a Comment