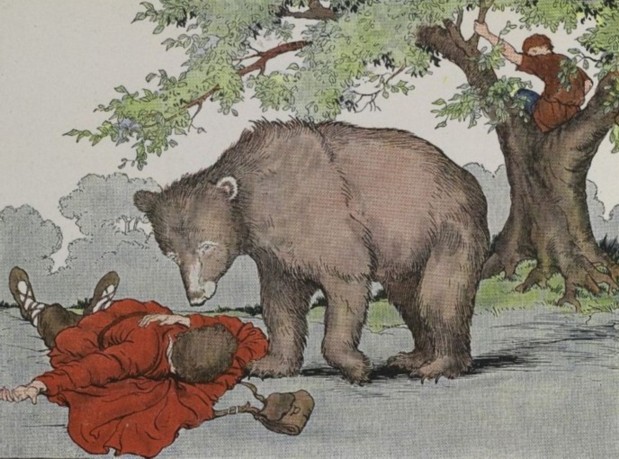

Today's fable is Perry #65, the story of two men whose friendship was put to the test when they ran into a bear unexpectedly on their travesl! At the Aesopus wiki, you can see a complete list of the versions of this fable that I have collected. This is a fable that enters into the Latin tradition by being included in the poems of Avianus. Avianus, however, is notoriously difficult to read, so I've decided to include here instead a very nice iambic poem by the Renaissance poet Caspar Barth:

Sodalitate mutua

Viam duo unam iniverant,

Fide data, ut periculis

Iuvaret alter alterum.

Parum viae cum itum foret

Fit obvia ursa: quae, prius

Inire quam fugam pote,

Prope ingruit. Tum in arborem

Levatus ille subfugit,

Supinus iste corruit,

Timore mortuum exprimens.

At ursa cum putaret hunc

Neci, olim obisse, traditum,

Anhelitum ore sublegens

Nec invenire eum potens,

Metu premente frigido.

Nec alterum altam in arborem

Pote esset usque consequi,

Utrumque liquit innocem.

Ibi ille qui alta in arbore

Periculum insuper sui

Amici habebat; Optime,

Quid, inquit, atra belua

Profundam in aurem, obambulans,

Tibi locuta sit, cedo.

At alter; a sodalibus

Cavere deinde ad hunc modum

Monebat infidelibus.

Pericla ni probant, fidem

Dare hanc sodalibus cave.

Here it is written out in segmented style to make it easier to follow, rearranging the Latin word as necessary to make the syntax more clear. Also, be careful with cedo - it is an imperative form meaning "come on! out with it!" (and so it is not a first-person indicative verb you might take it for at first).

duo

viam unam iniverant

sodalitate mutua,

fide data

ut iuvaret alter alterum

periculis.

cum itum foret

parum viae,

fit obvia ursa:

quae,

prius quam pote

inire fugam,

prope ingruit.

Tum

ille subfugit

in arborem levatus ,

iste corruit supinus,

mortuum exprimens timore.

at ursa

cum putaret

hunc olim obisse,

traditum neci,

sublegens anhelitum ore

et non potens invenire eum,

frigido metu premente.

et non pote esset

usque consequi alterum

altam in arborem,

liquit utrumque innocem.

ibi ille

qui habebat periculum

alta in arbore

insuper sui amici,

inquit:

"Optime, cedo,

quid

atra belua

obambulans

tibi locuta sit

profundam in aurem?"

at alter:

"monebat

deinde cavere ad hunc modum

a sodalibus infidelibus."

cave

fidem hanc dare

sodalibus,

ni probant pericla.

I like the way the quick-witted friend not only manages to escape the bear by playing dead, but also manages to come up with a witty comeback to his would-be friend as well!

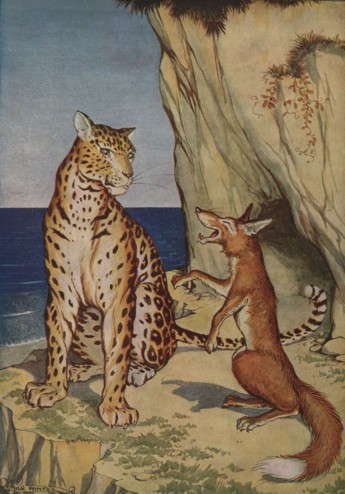

For an image, here is an illustration from Milo Winter's Aesop:

Some dynamic content may not display if you are reading this blog via RSS or through an email subscription. You can always visit the Bestiaria Latina blog to see the full content, and to find out how to subscribe to the latest posts.